MOLDOVA’S FOREIGN POLICY: SMART DIPLOMACY FOR A STRONGER COUNTRY

Executive Summary

Moldova is engulfed in multiple crises. Some are immediate. Some are structural. In the short run Moldova’s foreign policy should be focused on (a) obtaining more vaccines for 2021 and pondering the need to place orders for vaccines for the next few years; (b) connecting Moldova to the pan-European effort to create a digital certificate that would allow vaccinated Moldovan citizens to travel freely; (c) putting together with international partners a significant economic recovery plan; (d) intensifying cooperation with law-enforcement agencies of other states to investigate Moldova-related money laundering and fraudulent money flows, trace and potentially recover stolen assets.

But Moldova cannot afford itself to deal with urgencies only. The country’s structural problems are so deep that they need to be urgently tackled as well. On this front Moldova needs to start preparing the groundwork for more systemic reforms that would potentially yield results in a few years from now. Reform of the justice sector is only the first step in Moldova’s wider reforms needs. There are plenty of states in the post-Soviet space, the Balkans or the Middle East and Africa that are less corrupt than Moldova but are not particularly dynamic economies anyway. Moldova needs a vision and conscious policies in many policy domains going beyond justice sector reform, on issues such as infrastructure development, environmentally friendly growth, or bringing Moldova into the digital age. The brief proposes the creation of a National Reform Council that would outline reform priorities and design legislative packages for much needed reforms.

To achieve these goals Moldova will need to subordinate foreign policy to the country’s domestic transformations. On this front Moldova needs to boost connectivity and strong political partnerships with its neighboring Romania and Ukraine, cooperate closely with the EU, US and international institutions in trying to modernize the country. This also applies to the need to modernize and consolidate Moldova’s security and defense sector, not least through greater international cooperation. At the same time, it is important, when possible, to minimize friction, with other partners, including Russia. This might be difficult, not least because of Russia’s own foreign policy choices, its illegal military presence in the Transnistrian region, the lack of conflict-settlement in Transnistria and support for corrupt political forces in Moldova. At the same time, the absolute majority of Moldovan politicians cannot ignore the fact that a large part of public opinion prefers to avoid crises with Russia, be it on the diplomatic, economic or security front. Moldova should also capitalize on the added value stemming from the regional approach. This would mean that Moldova’s diplomacy should find tools and synergies in advancing economic, infrastructure and transport projects. None of these objectives are achievable without an active foreign policy, which needs to be principled, predictable and consistent.

This policy brief was developed in the framework of the project „Policy bridges with the EU: Securing the Europeanisation process of the Republic of Moldova” implemented with the support of the Soros Foundation Moldova. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone.

Introduction

On 27 August 2021, Republic of Moldova will celebrate the 30th anniversary since the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. By that time, the country will also have a new parliament, and possibly a government. By late summer, Moldova will have a chance to finally design a foreign policy that is capable of boosting Moldova’s transformation into a better governed, more democratic and more prosperous state.

A mixed foreign policy legacy

Ever since 2005, Moldova’s foreign policy was shaped by the European integration objective. However, the consistency of Moldova’s pro-European foreign policy had to suffer because of high levels of corruption, anti-European practices in domestic politics, and at times open attacks against the EU from influential political players. The billion-dollar banking fraud exposed systemic corruption problems and shattered high expectations. From 2015 onwards, the EU and other international development partners started to apply stricter conditionality, linked to results of the reform process, the respect for democracy, rule of law and human rights. This was an important leverage factor for the governing elites in Moldova to stay on track of reforms and sanction them when democratic principles were violated.

In recent years – when Moldova was governed by Plahotniuc and/or Dodon – under various configurations, the country grew increasingly isolated on the international arena. One claimed to implement a pro-Western foreign policy, and the other claimed to seek a ‘balanced’ foreign policy. Both failed to either bring Moldova closer to the EU or retain a healthy balance between East and West. Both exploited divisive geopolitical messaging to gain domestic and international advantages for personal benefits. Anti-Europeanism and anti-Russian sentiment are not significant mobilizing factors in domestic politics. Both did much to discredit the notions of either a ‘pro-European’, or a ‘balanced’ foreign policy, because these terms were used to disguise corruption and an incapacity to achieve results. Though disinformation still is a big challenge, Moldovan citizens start to better decrypt the intentions hidden behind these narratives, striving for policies that help to address real systemic problems of the Republic of Moldova, such as corruption, politicized institutions and unfair justice.

The unprecedent vote of almost one million citizens for Maia Sandu as President of the Republic of Moldova, is yet another confirmation of the new trend. Moldovan society is now opting for leaders that are inclusive, have a pro-reform and anticorruption agenda, inspiring internal transformations and promoting a positive foreign policy aimed at putting Moldova on the map of more resilient, developed and democratic European societies. The first 100 days in office of President Maia Sandu is paving a solid track towards this objective.

The special strategic partnerships with Romania and Ukraine were relaunched. Romania was among the first EU countries to provide consistent support to address the pandemic crisis needs and provided the first lots of anti-COVID19 vaccines. The high-level political dialogue with the EU and its member-states including with France and Germany was reestablished aiming at advancing political association and economic integration, but also supporting the pro-reform agenda of the President. The new administration at the White House provides for a great momentum for an upgraded bilateral partnership with the US, which could rely on an even stronger support for Moldova’s security, economic development, rule of law and anti-corruption efforts. However, the crisis environment significantly complicate Moldova’s capacity to implement an efficient and result-oriented foreign policy.

Navigating through multiple crises

Moldova is a country of multiple immediate and structural crises. All of these crises are leaving a huge imprint on Moldova’s foreign policy – its priorities, tools, and capacity – to implement policies or even think strategically about the country’s place in the world.

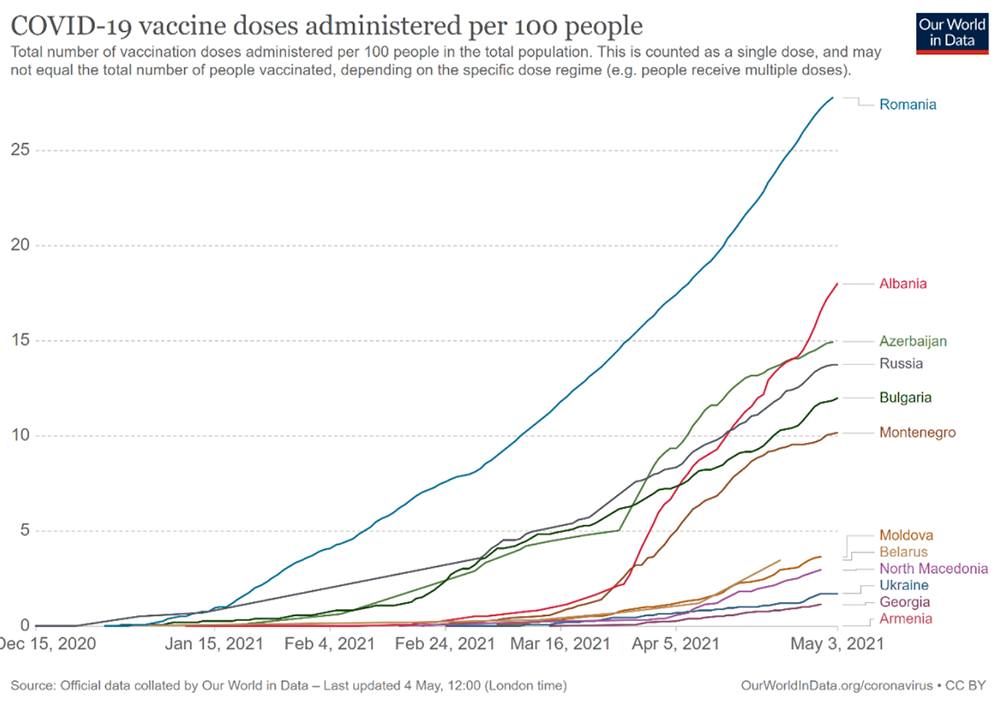

The country faces three immediate and mutually reinforcing crises. First, is of course the COVID pandemic. Moldova’s healthcare infrastructure has been submerged in the pandemic wave. Excess mortality was high and the capacity of the country to deal with this pandemic wave is still very limited. Access to vaccines has also been complicated and relies mainly on the external support. Romania donated a crucially important 200.000 vaccines. Recently, Romanian Government announced a new donation lot of 100.000 anti-Covid vaccines and the readiness to provide 200.000 shots every month at the EU negotiated price. Moldova has also been one of the first countries to receive vaccines through COVAX platform, namely 88.000 vaccines as of April 2021. Overall, the COVAX platform is supposed to cover 20% of the country’s vaccine needs. Russia donated 142.000 doses of Sputnik-V. China also donated 150.000 Sinopharm vaccines and sold 100.000 doses of Sinovac. When it comes to the vaccination rate, Moldova certainly lags behind EU member states, and some Balkan countries, but still managed to have the second highest vaccination rate per capita among the Eastern Partnership countries (after Azerbaijan).

Today, the key challenge remains how to cover the entire vaccination need of Moldova. In 2020 the authorities have not done much to put Moldova in the global queue for vaccines. Moldova also doesn’t have the financial means to overpay significantly for vaccines as many richer states seems to have done, nor the weight to negotiate good prices as the EU did. And even if Moldova’s acting government allocated 60 million MDL in March 2021, this is not enough. On the other hand, COVID-19 also significantly disrupted international diplomatic travel, which again restricts Moldova’s capacity to reset, consolidate and develop foreign partnerships.

Second, the economic repercussions of COVID itself, as well as the possible delayed vaccination of the country are all having significant negative effects on the country’s economy. Already in 2020, due to very limited access to international financial assistance the Socialist run government at the time has offered virtually no help to the economic actors suffering from the pandemic. In the second half of 2021, Moldova’s access to international assistance might improve, but mobilizing external support directed at overcoming the health and economic effects of the pandemic is still likely to consume significant energy in the country’s foreign policy.

A third immediate crisis is generated by the deep political standoff between a reformist president and political actors opposing the anti-corruption agenda for which the president was elected for. Early elections will take place on July 11, 2021. The Party of Action and Solidarity, formerly headed, and now supporting Maia Sandu is well placed to be the biggest force in the parliament, but it remains to be seen if they will have enough MPs to have a majority on their own or might need to form possibly complicated coalitions. Either way, it will take time to form a government, appoint state secretaries (i.e. deputy ministers) and heads of agencies. So, Moldova will still start having a fully functional parliament and government in autumn only.

These three immediate crises – pandemic, economic and political – are only the tip of the iceberg. They are just the visible part of several deep and systemic crises of virtually all Moldovan public institutions. Corruption has been pervasive for decades and has aggravated in recent years. The efforts to at least try to recover the stolen billion are at their incipient stage. The justice sector is in a deep crisis. Frequent government changes and altering governing majorities in the last two years or so, also left many key capitals without Ambassadors, among them Bucharest and Paris, while political appointees in some other capitals, are not likely to last.

When it comes to foreign policy, there is certainly a deficit of trust. In the early 2010s several successive Moldovan governments implemented a very active pro-EU foreign policy and branded Moldova domestically and internationally as a major success story in the EU’s Eastern neighborhood. Foreign dignitaries were not shy in praising the Moldovan authorities, but at the same time a billion dollars were stolen from the country’s banking system. This significantly undermined international trust in Moldova as a country, but also public confidence in proclamations of foreign policy successes or pro-European declarations.

Between 2016 and 2020, former president Igor Dodon was shunned quite a lot on the international arena. First, because of a strong record of anti-European, anti-Romanian, anti-Ukrainian and anti-American statements, and later because of strong allegations of corruption. Moldova’s diplomatic capacity to develop bilateral relations with many key partners was limited.

For various reasons in the last decade or so, Moldovan public opinion developed an excessive and unhealthy dose of skepticism vis-à-vis pro-active foreign policy efforts. This legacy also casts a shadow on the country’s capacity to conduct an active foreign policy. Now each trip of the new President, Maia Sandu, is being carefully scrutinized and there is constant pressure to look at foreign trips through the prism of insufficient immediate quantifiable results. But of course, any significant foreign policy benefits need multiple diplomatic efforts, not just one-off occasional trips. The reality is that the foreign policy is a process in which you have to invest a lot today to get concrete results in a few months or a few years later. And in this sense, active diplomacy is an investment which already brought already some immediate results, including, for example, accessing the first shots of much needed vaccines. But laying the groundwork for longer term partnerships through an active foreign policy, would be even more important than obtaining vaccines. Without these partnerships Moldova will struggle, because it does not have sufficient internal resources to survive in isolation and without external support.

Conclusions

Over the years, Moldova has built a reputation as a rather unreliable and inconsistent international partner. Words and deeds often didn’t match, and domestic actors often manipulated foreign policy discourses for political or even personal gain. This year Moldova has a good chance to start correcting this legacy.

The success of any foreign policy is shaped by the ingredients of the country’s internal policies. The internal political turbulences and lack of a consistent track-record of reforms may definitely be the explanation for not reaching the desired balance in external affairs, nor to achieve its key priorities. Moldova’s territorial integrity is still challenged. Systemic corruption, cases of violations of human rights and unfair justice is symptomatic of the state of the rule of law in the country. The country’s economy is still struggling. Even though Moldova today is on track of legal approximation of the EU’s acquis and has access to a huge non-exclusive market, thanks to the to the Association Agreement with the European Union.

When there is a new government in autumn, it would be useful for the country if the three main branches of power – the presidency, the government and the parliament – work together to review and upgrade Moldova’s national foreign and security policy guidelines. In the meantime, given Moldova’s multiple crises – epidemiological, economic, political, and institutional – the country’s foreign policy has no choice, but to adapt and tackle to these constraints.

What is clear is that in the next few years Moldova should seek to deconflict as much as possible its diplomatic interactions with its foreign partners. If reforms continue, and especially if President Maia Sandu will be able to rely on a reformist majority in the Parliament, there are few risks of diplomatic tensions with the EU and the US. The situation is much more complex when it comes to Moldova’s Eastern partners where relations are particularly complicated with Russia, but even relations with Ukraine are not always easy.

Key Recommendations

In the short to medium-term, tentatively until the end of 2022, Moldova’s diplomacy should first deal with the country’s immediate and structural needs. This will also lay solid ground for longer-term successes domestically and internationally, as soon as a new pro-reform government will be in place. To support the later, a set of recommendations on basic principles for an improved Moldova’s foreign policy are presented, as well as key priorities deriving from multiple crisis.

- Key principles of Moldova’s future foreign policy:

- Moldova needs more than ever an active foreign policy in order to mobilize international support that could help the country overcome its multiple crises, but also years of mismanaged foreign policy efforts. It remains to be seen if the public opinion constraint on foreign policy will gradually subside or persist, but it is clear that politicians have to keep an eye on public opinion on this matter. Moldova’s capacity to implement an efficient and result-oriented foreign policy should be strengthened.

- Promoting a positive foreign policy in particular in times of regional and global challenges is key. Moldova should contribute to a non-conflictual environment in its relations with all regional and global actors. At the same this might not be always achievable, and the pursuit of smart and respectful diplomacy should certainly not entail any compromise with the country’s core national interests. For that reason, it is crucial for Moldova to build-up solid and long-term value-based, economic and security partnerships with friendly countries.

- Moldova’s foreign policy needs to be principled and predictable. It should be guided by clear priorities to strengthen internal resilience, make full use of the opportunities provided by international partners to advance the economic and democratic development of the country, and strengthen its resistance against external hybrid threats. Moldova’s foreign policy should be a key instrument to protect and bring clear benefits to its citizens.

- Moldova’s foreign policy should be In Moldova, the Parliament approves the main foreign policy guidelines, the Government ensures their implementation, while sharing with the President of the country some of the foreign policy competences in terms of holding negotiations and signed international treaties, appointing ambassadors abroad and receiving credentials from diplomatic representatives of other states. Often times, key Moldovan foreign policy actors, in particular President and Government were sending abroad different messages. This affects Moldova’s external credibility as a reliable partner and undermines the efficiency of Moldova’s foreign policy efforts. This should be avoided in the future. All relevant actors have to overcome internal political disagreements, agree on the key national foreign policy priorities and implement them coherently. Clear institutional cooperation protocols and operational guidelines for the foreign policy implementation efforts should be agreed among the President and Government in particular with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration.

- Moldova’s bilateral partnerships are key to preparing the ground for future successes. Take relations with Romania, which has offered Moldova enormously valuable help during COVID pandemic, not least a very high number of vaccines. While dealing with such urgencies, it is absolutely crucial to spend significant amount of time in preparing the ground for longer-term goals such as better connectivity with Romania. If Moldova wants more bridges with Romania, one or two highways connecting Chisinau to Iasi and Bucharest, in a decade from now, the authorities have to start acting now. Thus, it is important to keep the momentum on preparing future join infrastructure projects with Romania, while also tackling immediate challenges. The same goes for Moldova’s relations with Ukraine.

- Think big and 20 years ahead, when it comes to strategic bilateral priorities and projects with Romania and Ukraine. As part of this exercise, it is perhaps useful to start developing a vision that also accounts for potential high-speed rail connection to Bucharest and Kyiv, highways, and new bridges. The main railway connection between Moldova and Romania has been built 140 or so years ago by Gustav Eiffel, who also built the Eiffel tower in Paris. The two countries certainly deserve newer infrastructure connecting them.

- Moldova’s foreign policy needs to converge with the opportunities that are shaped by the next top priorities of Moldova’s European and Transatlantic partners. New deliverables for the Eastern Partnership policy will be agreed later this year. Moldova and the EU will adopt soon the new Association Agenda aligned with EU’s budgetary priorities by 2027. A new Conference on the Future of Europe was launched and given its European integration objectives, Moldova along with other aspiring Eastern Partners should be included in this process. This year’s NATO Summit is yet another opportunity that should be carefully considered. On the other hand, the unstable and security environment to the East and in the wider Black Sea is another factor that should be assessed, while adjusting the foreign policy priorities.

- Moldova should capitalize on the added value stemming from the regional approach in promoting its foreign policy objectives. Moldova is too tiny to be effectively reaching out to global actors to attract the necessary attention and support to successfully implement its domestic and foreign policy objectives. A regional approach would mean that Moldova’s diplomacy should find tools and synergies in regional and multilateral partnerships advancing economic, infrastructure and transport projects, which are key to its economic recovery and becoming a connecting hub between East and West. This is also relevant to security objectives. Exploring the importance of the security in the Black Sea region is paramount. Moldova should integrate within regional security structures and initiatives, being more of a partner than only a security beneficiary.

- Foreign policy priorities deriving from immediate and critical needs:

Vaccination

- Seeking to vaccinate most of the population by using active diplomacy. This has been happening already with relatively good results. In the following weeks and months Moldova will need to seek actively both donations of vaccines but also vaccines able for sale and would need to look for ways to buy them at reasonable prices. But vaccination might not be a one off. In 2020 the Moldovan government did not order vaccines. It is important to avoid a similar problem in 2021. In all likelihood, vaccines might be needed for the next years, and perhaps further. The EU seems to be starting negotiations to order vaccines for 2022-2023. If Moldova is to avoid finding itself without vaccines in future rounds of vaccination in say 2022 or 2023, it would be useful to start assessing whether the country needs, and possibly pre-order vaccines for the next years as well.

- In light of the fact that many countries, particularly the EU member states, have started developing digital vaccination certificates, it is crucial to start connecting Moldova to this process, by developing a national a digital vaccination certificate and making it compatible with those of the EU, Ukraine, Russia and Turkey, which are the most important travel destinations countries for Moldovan citizens. It should imply physical safety features, QR-codes, but most important an integrated database of vaccinated citizens. In any case, Moldova needs to start looking for such technical solutions as soon as possible, or risks not being able to benefit from unhindered international travel on a par with vaccinated citizens of other countries.

Internal political and systemic reforms

- Despite dealing with urgencies, and there always are urgencies, it is of crucial importance for Moldova to start preparing the groundwork for more systemic reforms that would potentially yield results in a few years from now. These preparations cannot wait until the pandemic will be over. It is important for Moldova to start preparing such a reform package already now. Working on a reform blueprint today would save a precious time for when a more a reformist government would come to power. One way to go about it, is for the President to create a consultative National Reform Council, modelled on a similar body in Ukraine, which would start developing reform-minded legislation.

- Moldova needs to start working on a comprehensive reform package that goes significantly beyond just justice sector reforms and anti-corruption. Anti-corruption is a major national priority and will remain so. While justice sector reform is an absolute precondition for any credible reforms, such a reform in itself might not be enough to help the country make a dramatic leap forward. Even if and when there will be some successes on the justice front, these successes will not automatically, as if by magic turn Moldova into a prosperous country. They will turn Moldova into a better run country, but not necessarily a massively more modern one. Let’s assume in a few years’ time Moldova, which is 115th place on the TI Corruption Perception Index, manages to significantly reduce corruption and climb to the 70th or 80th place in the world. That would be good, but not enough. If Moldova would manage such an improvement, it would still be in the category of states such as Ghana (75), Argentina (78), Benin (83), Lesotho (83), Morocco (86) or Burkina Faso (86) when it comes to corruption perception levels. It would still have a much worse corruption situation than Botswana (35th place), Georgia (45), Rwanda (49), Armenia and Jordan (60), or Montenegro (63). In other words, even in the best possible case of anti-corruption reforms in the next 5-10 years, Moldova will still be just a middling country worldwide, and will still need pro-active policies and innovative reforms to attract investors generate jobs, build infrastructure, connect the country to the digital era, or implement environmentally friendly growth models.

- Operational civil and criminal international cooperation is crucial for advancing effective investigation of frauds and recovery of stolen funds by Moldova’s justice, law enforcement, security and intelligence actors. The same is relevant to the fight against systemic corruption, ensuring more effectively the integrity of politically exposed persons (PEPs) and justice actors. Trace down and expose assets of unexplained origin, hidden abroad ,should be another priority of the international legal cooperation.

- The country also needs a comprehensive reform of its security sector. Corruption is of course a major security threat but is not the only. Moldova needs a capable security sector – army, intelligence service, police – able to withstand not just corruption but also hostile behavior by foreign countries, be it in the form of hybrid interference, subversion of state institutions, or hostile actions by foreign intelligence agencies on Moldovan territory. The security and foreign policy priorities should be harmonized.

Economic recovery and sustainable development

- Attracting foreign assistance is crucial to overcoming the crisis and ensure Moldova’s sustainable development for the years to come. Moldova needs an investment and economic recovery plan to be supported by the EU, IMF and other international partners. It should help Moldova to address the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed serious systemic problems in the Moldovan economy, affected human rights, fair distribution of resources and social inclusion. The EU is already working on a special plan to support the immediate specific needs to help Moldova’s economic recovery. The Association Agreement with the EU and the new Moldova 2030 Sustainable Development Strategy aligned with SDGs, already provides for a solid ground in this regard. Foreign direct investments are crucial for the sustainability of Moldova’s economy. Integrating Moldova into shorter value-production chains of the established international enterprises and relocating their production in Moldova from other places should be one of the key priorities for Moldova’s economic diplomacy abroad.

About the authors

Dr. Nicu Popescu is the director of the Wider Europe programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR, Paris). He holds a PhD in International Relations from the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary. In 2019, Popescu served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration of Moldova. Previously, he worked as a senior analyst at the EU Institute for Security Studies; senior advisor on foreign policy to the prime minister of Moldova; senior research fellow at ECFR’s London office, and as a research fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels.

Iulian Groza is an expert in international relations, European affairs and good governance with a particular focus on EaP countries and the EU. He is a former Deputy Foreign Minister of the Republic of Moldova in charge for European integration and international law. Currently, Iulian Groza leads the Institute for European Policies and Reforms (IPRE). He also is a Board member of the Institute for Strategic Initiatives (IPIS). Mr. Groza holds a University Degree in Law. He also did postgraduate European Studies at Birmingham University and NATO Security Studies at SNSPA in Bucharest. He is a Jurist Doctor candidate in law at the Moldovan State University.

Fullscreen Mode